Move Over Selenium, Cypress is Here

I love pragmatic solutions and if you’ve read some of my prior articles (Write Less Code, Making the Complex Simple…), I often look for tools and solutions that have an easy barrier to entry, avoid complexity, and allow developers to do their jobs. In the world of browser-based end-to-end testing, Selenium has been king. If you mention automated testing you will typically hear Selenium first followed by a few other commercial and open source products. I have used Selenium with various language bindings (Java, JavaScript, Ruby) on different projects and always ran into lots of issues with timeouts, tests taking too long, and strange inconsistencies with results. This may not be everyone’s experience, but it has certainly been mine. This article is not a bashing of Selenium since I do think it’s king for many reasons, but when something comes along that seems better (less complexity and better consistency) then I enjoy sharing the information with others.

Recently a colleague of mine mentioned that he was using this tool called Cypress. I gave it a go and was very impressed. Here is an overview including:

- What is Cypress?

- How does it differ from Selenium?

- Where does it fall short?

- Example tests using a todo application.

What can you do with Cypress?

Cypress is a UI end-to-end automation testing framework that is NOT built on Selenium. It actually runs directly in the browser (Chrome browser, more on this later). Developers and/or QA Engineers can write and run unit tests, integration tests, and end-to-end tests. It’s for developers to do pure TDD while building an application and then run and record those tests in a CI/CD environment where failures are easy to debug. Developers write the tests in JavaScript using familiar tools like Mocha (test framework) and Chai (assertion library) and maybe a not so familiar Sinon (mocks, stubs, and spies) and use jQuery selectors for finding elements in the DOM.

How is Cypress different from Selenium?

- Most importantly, Cypress runs in the browser so it has access to the application and everything in the browser. Because of this, many of the items below are possible.

- Cypress allows you to bypass logging into your application (a common delay with testing using Selenium since you typically need to login to your application to have access to functionality). Cypress can extract a cookie and just use it at will for future tests.

- With Cypress you can programmatically bring your application to its desired state. For example, instead of logging in and drilling down several pages, you can alter the state to begin where you need to start your testing.

- Cypress gives you the ability to really assist with testing during development and beyond including:

- Very fast – again because it’s in the browser.

- Records video by default when running tests command line – video of your tests running to allow you to see actual changes and help debug.

- No waits or sleeps! Again, since Cypress runs in the browser, these delays or hacks go away.

a) access to spies – for verifying that a function has been called;

b) stubs – to change the behavior of functions to aid in testing;

c) control over the browser’s clock – to allow you to simulate time passing; and

d) intercept and modify HTTP requests – as in the case to stub out the backend during development.

Let me go into detail with the login process to illustrate the benefits of using Cypress over Selenium. Those of you who have used Selenium or other testing tools are familiar with the additional overhead time required with the full process of logging in a user just to get to the point where you can test a functional page. With Cypress you have the ability to simplify, and more importantly, improve the speed of this process.

First, let’s take a step back and discuss the various options for dealing with authentication in Cypress:

- Stub requests – here we can just test the UI on its own and make sure no authenticated requests are being submitted to the server. This requires a bunch of work to do this but may make sense in certain applications.

- Seed the server with users.

- Dynamically create new users. This can be slow depending upon the server authentication process.

Depending upon your server situation you may use a combination of these three, but for the purposes of this article let’s assume we are going to seed the database with a few different users with different roles and attempt to login with each of those users as quickly as possible.

First, to seed the users, you have three ways to communicate with the outside world (outside the browser):

- cy.exec – to execute system command.

- cy.request – to make HTTP request.

- cy.task – to talk directly to Node.js (in plugins).

With any of these you can seed your database. We’ll assume that the authentication process from your login page is a typical one:

- Form submit with username and password.

- Post values to an API.

- On success, saves the token.

- All pages requiring a login user checks for the token.

Before we get to code, let’s organize how we are writing tests. Each spec file tests an individual page in isolation. This spec file will contain any number of individual tests for that page. The best practice is to then group these spec files by functional groupings into a folder. With Cypress, there is an index.js file that is loaded first. This is where your commonly used functions are stored (such as a login function).

Here is an example of a common login function you may have:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 | Cypress.Commands.add('login', () => { cy.request({ method: 'POST', url: 'http://localhost:3000/api/users/login', body: { user: { email: 'arthur@example.com', password: 'solutionstreet', } } }) .then((resp) => { window.localStorage.setItem('jwt', resp.body.user.token) }) }) |

You can then call this function from individual specs via cy.login(). The “magic” here is that we are using cy.request(). The cy.request() makes HTTP requests outside of any security restrictions, but it actually uses the browser’s user agent and cookie store. In this example we are actually logging in via the server without going to any login page and filling in the form, but you can see how this can be taken further to just set the token in local storage based on one that is valid without calling the API. Of course this may have its own set of issues, but the point is that you have deeper access to deal with bypassing traditional testing requirements to go to the login page, fill out the form, and submit.

The overriding concept of Cypress is that you have internal control so you can have direct access to any number of things the browser has access to including direct access to a Redux store and other internal access points used by single page application architectures.

Where does Cypress fall short?

At this point there are three obvious areas:

- Browser support – Cypress only supports Chrome currently but is expected to expand to other browsers.

- Cypress supports only plain JavaScript or Typescript, whereas Selenium supports more languages.

- Community – small community currently.

Additionally, Cypress does not have the ability to do record and playback (convert a recording of you testing in real-time into scripts), something that Selenium offers. However, I would attest to the fact that this capability is not used often for serious testing. Cypress offers the ability to easily find DOM elements and makes writing tests much easier.

Example – basic todo app

I wanted to test Cypress using a basic web app to get the flavor of what it can do. I chose to download a basic todo app running on Node and using MongoDB. You can follow along as well to see the basics of Cypress. Obviously you can test your own application, but I would warn against testing any public application that is not owned by you (e.g., google.com or facebook.com).

First, (as taken from the GitHub instructions for the basic todo app) perform the installation of the todo app:

Requirements –

- You must have Node.js and NPM installed – you can use any number of methods including here and here. You may already have these installed – NPM is installed with Node typically. You can type “node” and “npm” in a terminal to make sure you have them.

- MongoDB – make sure you have your own local or remote MongoDB database URI configured in config/database.js. Again, you may already have MongoDB installed or you can find one set of instructions here.

- Git.

Installation of todo app –

- Clone the repository: git clone git@github.com:scotch-io/node-todo

- Install the application: npm install

- Place your own MongoDB URI in config/database.js – mine looks like this:

- Change into the node-todo directory you just cloned and start the server: npm start

- View in browser at http://localhost:8080

1 2 3 | module.exports = { localUrl: 'mongodb://localhost:27017/todoapp' }; |

a) Note: in another terminal window you need to have MongoDB running if you don’t have it running in the background (e.g., mongod)

At this point you should be able to add items to the list and select them (checkbox) to be deleted. It will look something like this:

Now that we have our application to test, we can move on to installing Cypress and testing.

Installation of Cypress –

- In the node-todo project directory, run: npm install cypress –save-dev

- Now that you have Cypress installed for this project you can open Cypress via either:

a) npx cypress open (if your version of npm > 5.2); or

b) ./node_modules/.bin/cypress open

Cypress, like Selenium, is fairly easy to install. At this point your Cypress Test Runner is running and will look something like this (with various example specs already installed).

You can click on the “Run all specs” button in the upper right hand corner and see several dozen tests running for about a minute.

At this point let’s add a test:

- Open your node-todo project in your favorite editor. I’m using Visual Studio Code.

- In cypress.json at the root of the project, change the contents to be the following:

- Create an empty js file called ‘first_spec.js’ under the node-todo/cypress/integration directory.

- Within the file add the following code:

- Go to the Test Runner (scroll down to the bottom) and double-click on your file ‘first_spec.js’. This will execute your test in a new Chrome window. Note that at this point your test will constantly be running as you make changes.

1 2 3 | { "baseUrl": "http://localhost:8080" } |

This will set the base url of our todo application so that we can just reference the application by a basic root of “/” instead of the full url.

1 2 3 4 5 6 | describe('My First Test', function() { it('Visits my site and verifies text', function() { cy.visit('/') cy.contains('Todo-aholic') }) }) |

It will look something like this after its successful run:

All we have done here in the test is go to the url and verify the text “Todo-aholic”. Now change the text “Todo-aholic” to something else in your test file and save (e.g., “Todo-aaaaa”. Cypress will automatically run and show you a failure – takes a few seconds to fail since it’s handling the waiting and timeouts).

Now change the contents of ‘first_spec.js’ to be the following:

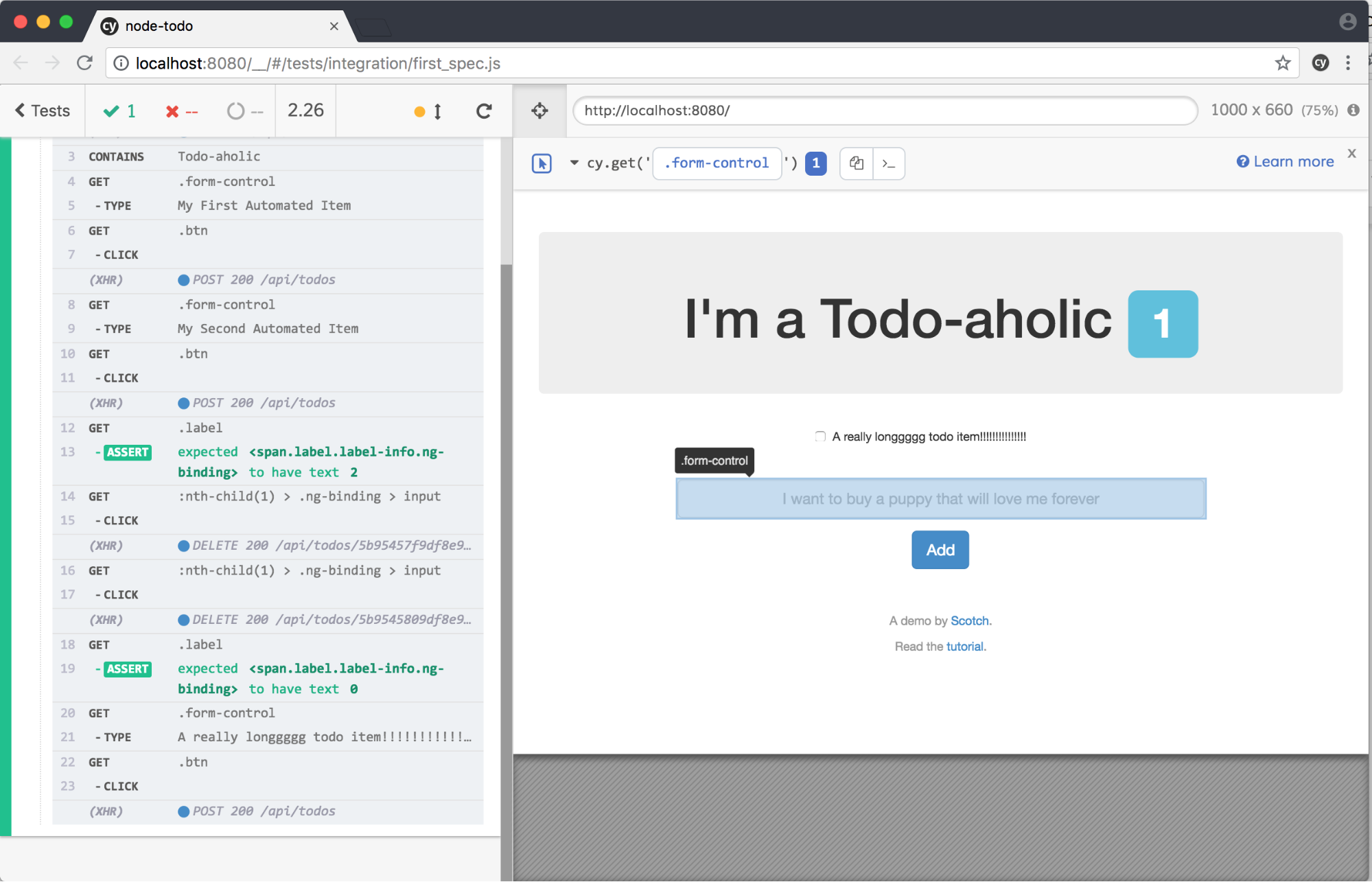

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 | describe('My First Test', function() { it('Visits my site and verifies text', function() { cy.exec('mongo todoapp --eval "db.dropDatabase()"') cy.visit('/') cy.contains('Todo-aholic') cy.get('.form-control') .type('My First Automated Item') cy.get('.btn').click() cy.get('.form-control') .type('My Second Automated Item') cy.get('.btn').click() cy.get('.label').should('have.text', '2') cy.get(':nth-child(1) > .ng-binding > input').click() cy.get(':nth-child(1) > .ng-binding > input').click() cy.get('.label').should('have.text', '0') cy.get('.form-control') .type('A really longgggg todo item!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!') cy.get('.btn').click() }) }) |

After saving, this should execute successfully. Let me discuss a few of these lines:

- cy.exec – This allows us to execute a system command – here I’m clearing out the database before each run.

- cy.get – Here I’m finding DOM elements; some simple elements and some more complex.

- cy.type and cy.click – Typing into fields and clicking buttons.

A full set of commands are listed here.

How was I able to identify complex elements? Cypress offers the ability to identify DOM elements easily. Within the Chrome browser that starts from the Test Runner, there is a button on top called “Open Selector Playground”. After selecting this you can hover over elements and see their selector paths. For example, here I am hovering over the text area where you type in a todo item to see that the selector would be ‘.form-control’:

One of the most powerful aspects of Cypress is that your tests are “recorded” in that you can hover over any step executed in your test code to see the state of the UI at that point. This is powerful for debugging purposes. Cypress should run on all continuous integration providers.

See here for more information on best practices.

Summary

Although I didn’t go very deep into many functions and features, you can clearly see the power of the tool. With deeper aspects of stubbing, mocking, and spies, Cypress becomes more powerful in its usage. Cypress is certainly more of a developer’s type of testing tool than Selenium – which many would consider a QA tool – but the need for a pragmatic UI-based unit/integration/end-to-end testing tool is much needed with today’s complex UIs. There is no question that being in the browser is much better for testing more dynamic UIs with single page application architectures. I don’t know if Cypress will ever take the lead from Selenium, but I do know that I will be suggesting the use of Cypress over Selenium for testing.